Helsingør: Pre-festival

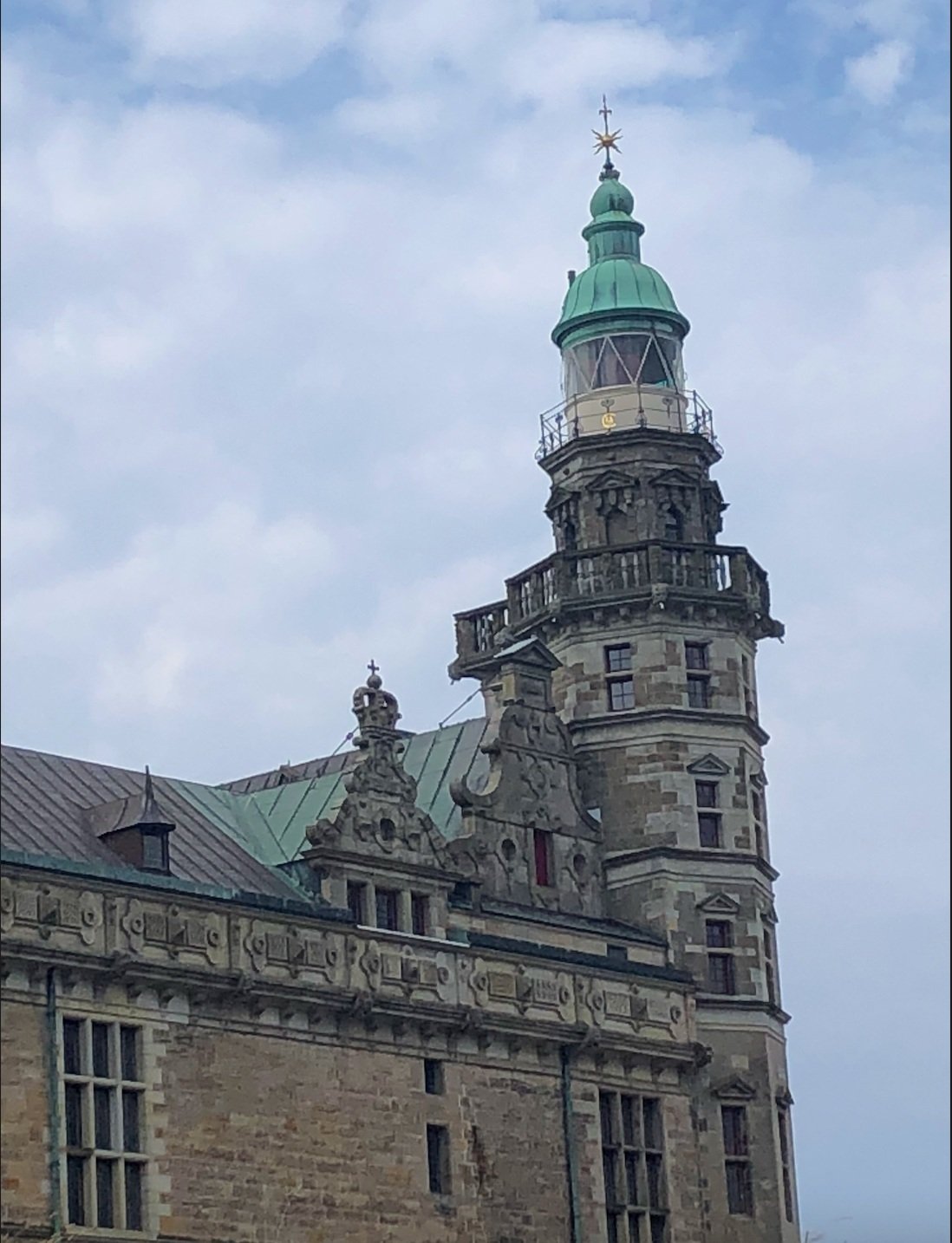

Elsinore, the name of Hamlet’s Castle, was inspired by the real castle Kronborg Slot, which is located in the Danish city of Helsingør (also called Elsinore). The city of Helsingør is located on the east coast of the country, facing Sweden, right on the Oresund (the Sound that lies between the countries), about an hour’s transit journey north from Copenhagen. The distance between Helsingør and the facing Swedish city Helsingborg is only 4 kilometers, and in fact there’s a ferry that travels between Helsingør and Helsingborg that takes about 20 minutes.

From the 15th to 19th centuries, Denmark had control over the Sound by way of the Kronborg Castle: it was able to charge a toll for every ship that passed through, and had cannons ready to fire at any ship that attempted to pass without paying. So, long before Shakespeare romanticized the castle into the familiar Elsinore, it was a significant source of Denmark’s income as well as for its political power. Through this toll system the country could favor certain nations over others, and ultimately form alliances.

I had no idea about the Hamlet connection to Helsingør before I arrived to the little city, and it gave me a welcomed sense of auspiciousness. Not only has the play been resonant with me since I first read it in high school, but, having reread it during the earlier stage of my journey, the figures, the rhythm, and the auric colors have kind of naturally moved adjacently with me as one of the few constants as I’ve been nomadic.

The previous Copenhagen post covered the first 5 of my 10 days spent in Denmark, and this post covers (the first half of) the next 5 days, which I spent primarily in Helsingør volunteering at the street performance art festival “Passage”. Ada had heard about it on a whim from a friend and I contacted them, having no idea what to expect but hopeful about the prospect of having some purpose, for which I was still desperate since before the Scotland fiasco. I continued staying with Ada and commuted up each day.

The headquarters of the festival was at a venue called Toldkammaret, a cultural center in Helsingør that organizes and hosts events and programs throughout the year. When I arrived the first morning, there were only a few staff members around and they were all quite surprised that an additional volunteer had shown up, and shocked that it was much less someone from New York. There was seemingly only one other volunteer, an elderly Danish woman named Malene.

This man would sometimes show up throughout the week, filling the role of “the old kind of creepy guy who randomly shows up sometimes and doesn’t do anything but babble on about nonsense to anyone who will listen.”

One day a sea bird got inside and the guy proceeded to feed it some bread.

So it continued.

I was underwhelmed by the volunteer situation and getting annoyed.

But soon after I concluded I would not be returning the next day and started trying to figure out what I would do with myself for the next number of days, a big group of people suddenly came filing into the room, seemingly all around my age. This was encouraging. They were clearly part of a temporary program because they were all familiar with one another, but I could tell that they were pretty newly acquainted. Some of the festival coordinators finally commenced our meeting and explained that the group was participating in a dance “camp”. Indeed, the people in this camp were from all around Europe: France, Poland, Croatia, and Austria, and part of their program was to help out with the festival (though for some reason they were considered “crew”, and paid an arbitrary 9 euros a day (??) while Malene and I were “volunteers”.)

Throughout my time in Europe, two things I’ve learned are: 1) Saying you are from the United States loses you about 15 points; 2) Saying that you are from New York City gains you about 25. The clout I got from stating New York origins was especially extreme with this group of peers. I could actually sense acutely that I was at once regarded as interesting and cool, of which I took complete advantage to splurge on confidence with some euphoria included.

For the first time in the past two months, I was finally in a systematic social environment where not only did I have a role and a presence but I was suddenly the person who people wanted to get to know, as the group had already been together for a week and I was the random girl from New York who intimidated people with her English (I was later told by several) and came off very confident — it was all the very opposite of the anonymity of which I had grown so tired. I was finally able to thrive in the ornate and circulative energy typically exuded from a large enclosed group of people.

In many ways, it was the very opposite kind of exhilaration that I get from being alone in a city. It’s as if there is a spectrum of a kind of exhilaration whose one end comes from the energy of a city, and whose other comes from the sudden immersion into a group where one is initially anonymous and quickly exposed — exactly like this. I suppose the latter end could be used to describe many new starts, but this situation was especially exhilarating for me, probably due to a combination of having been deprived of the terrifying and exhilarating pressure of presenting myself, lucky timing of my emotional cycles, and a tedious culmination of other reasons to forgo dissecting.

The first two days of volunteering were devoted to setting up the headquarters and the sites of the various performances, and then the festival would really begin on the third. It seemed like the staff had some loose plan for the camp people (whose badges said “crew”; mine and Malene’s said “volunteer”), but the “volunteer coordinator” (who was effectively the coordinator solely for Malene and me) was really off her rockers (she was always talking to herself… at one point I heard her mumble: “I need to get something to do something”) so Marlene and I were basically at liberty to do whatever we wanted. I spent the morning with the few camp people who were assigned to stay at Toldkammaret, moving chairs and tables from the courtyard into the dining rooms, hanging up flags, and trying to fulfill some tablecloth vision that no one seemed to understand. It was all great fun.

Tablecloth project.

The dining room where staff would eat. Bar is visible in the back, to be relevant during upcoming evenings.

For some reason there were several chefs who were employed solely to make food for all the staff, camp, and volunteers during the week. It was all vegan and extremely repetitive, but nonetheless great. A grand and extensive reunion with baba ganoush, hummus, and harissa.

I also hung up string lights with Malene. She used to make chandeliers so the task got pretty intense.

At the Maritime Museum, a few minutes’ walk away from Toldkammaret and right across from Kronborg Castle, on the first day after working. Tim on the left and Marlene on the right.

It’s a cool building.

It was designed by Bjarke Ingels, who has designed a slew of well known buildings, mostly in Copenhagen and New York. I read a bit about him afterward and find it interesting, so I’ll share a bit. He has coined the terms “pragmatic utopianism” and “hedonistic sustainability.” About one of his residential buildings in New York, he’s states that it “combines the density of the American skyscraper with the communal space of the European courtyard.” He is also the architect of the famous and bizarre Copenhill power plant-ski slope (one of its extremities was subtly pictured in previous post): it is the cleanest waste-to-energy power plant in the world with an artificial ski slope on top.

A nice diorama of a harbor.

When I arrived at Toldkammaret the next morning Malene was there, but after some time it became evident that the camp was not coming and it was to be only the two of us. The staff, bustling (or wandering) around, were not at all concerned with us. I thought this whole thing was just hilarious, as did Malene, which was the catalyst of our bond to form. I spent the morning hanging up posters on huge windows, which was enjoyable because no one could be bothered to give me any direction, and Malene made who knows how many pots of coffee (I’m also not sure who was continuously drinking it) — she had this great kind of juvenile sense of humor sometimes — and we ironed some extraneous table cloths to pass time until lunch.

I got some clarity on what the festival was all about. It was to last over four days, and was comprised of a huge lineup of site specific performances taking place all around the Helsingør area. All of the performance groups were independent, which the festival organizers had discovered and rounded up during the past year. If it was indeed practically a manifestation of my fantasy, it was like a scavenger hunt of performance, tucked away in corners or perhaps bizarrely in plain sight, and one would have no idea about what to expect until arriving (though if one knew Danish and could read the program prior, it was possible to get a gist — so in the end I got a fuller scavenger hunt experience.) To me it all sounded too good to be true, and that first day of bonding and performing alone was the best day I’d had in a long time, and so I was not holding my breath for anything extraordinary.

It turned out that the camp had been preparing to perform a piece over the past week and were to perform it that afternoon in an outdoor space adjacent to the Maritime Museum, thus why they were not volunteering that day. It was not technically part of the festival but was clearly inspired by it, which somewhat clarified why they were in a separate category from Marlene and me. She and I walked over together.

I was not pleased with the piece. Sometimes I find it energizing to see dance (and art in general) that I don’t like — as Barry told me once, it is just as valuable to see dance you dislike as dance that you are really drawn to. And I think this sentiment can be applicable to many things, like working a job you quickly deem repressive, and reading an infuriating book, and having a friend you eventually realize is not one to keep. But this performnce just made me annoyed. It was in a cool space, it included audience participation, they used a mixer to create audio in real time, and most importantly it was a big group of artistically minded people. But it was underwhelming and it was the kind of artistic work that give a nod toward being both meaningful and provoking, but by not quite achieving either it actually swipes out the little preliminary flame that could have been so nurtured.

I’m sure this reaction sounds harsh. I express it to its full extent because it was in fact an important part of my experience of the progression of the week. At this point, between the poor organization for the volunteers and this piece, I was progressively considering the festival as more endearing than anything very personally artistically fulfilling — with which I was relatively content. I had already benefitted from sourcing a great deal of energy from the experience.

Malene and I shared our similar views about the piece on our walk back to Toldkammaret, and I was starting to sense our likemindedness, not just in our tastes and approaches but in the subtle ways that are difficult to articulate — those that wildly accelerate the development of a relationship. Since neither of us had any arrangements for the rest of the day, we decided to go together to the Louisiana, one of the country’s great museums, and afterward to a rehearsal of one of the Passage performances. (Some of the more technical performances had rehearsals before the festival actually began.)

I will proclaim that the Louisiana is my favorite museum I have ever visited. It was the perfect size: five supreme exhibits with a small scattered permanent collection.

From the permanent collection: famous Danish artist Asger Jorn.

There was an immense exhibition of Alex Da Corte, a Venezuelan-American artist, titled “Mr. Remember”. He works with a slew of different media, always creating some sense of being in an alternate fantasy reality yet grounded in something of his intricate inner world. His work reminds me of a blend of Warhol, Jeff Koons, and a forceful presence of yearning and pain and momentum.

On the surface, he serves indulgence — many people throughout the exhibit were visibly transfixed as if they wanted touch things, or climb things, or take things, or somehow participate with the pieces — including myself. There was an alluring and addictive quality to everything. And simultaneously, there is something of a message of caution in his art, a confrontation of our attachments and gluttony.

I was very taken.

Some of his installations in the first room:

I include only because it’s called “Everyone Finds Love in the End.”

~heartily dedicated to my Uncle Andrew.

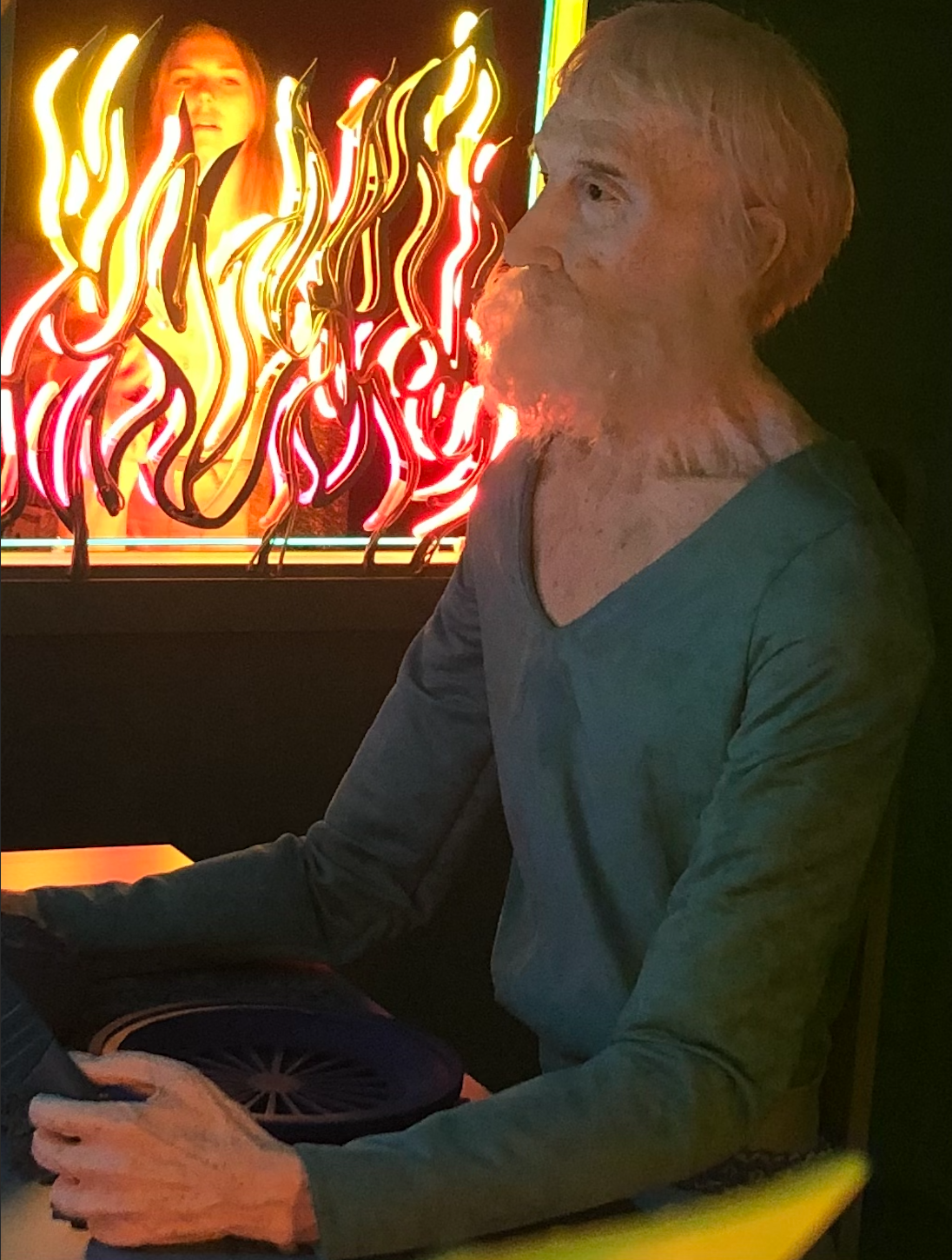

One animate; one inanimate.

This installation was especially curious. The man is sitting inside a house-structure at the head of a long table that is covered with an arrangement of objects like plants and a rolling pin and humping bunnies and half of a disco ball, all illuminated in neon blue light. The house had six windows, all equipped with this neon fire. I took this photo through one of the windows, and this girl was looking in through the window across.

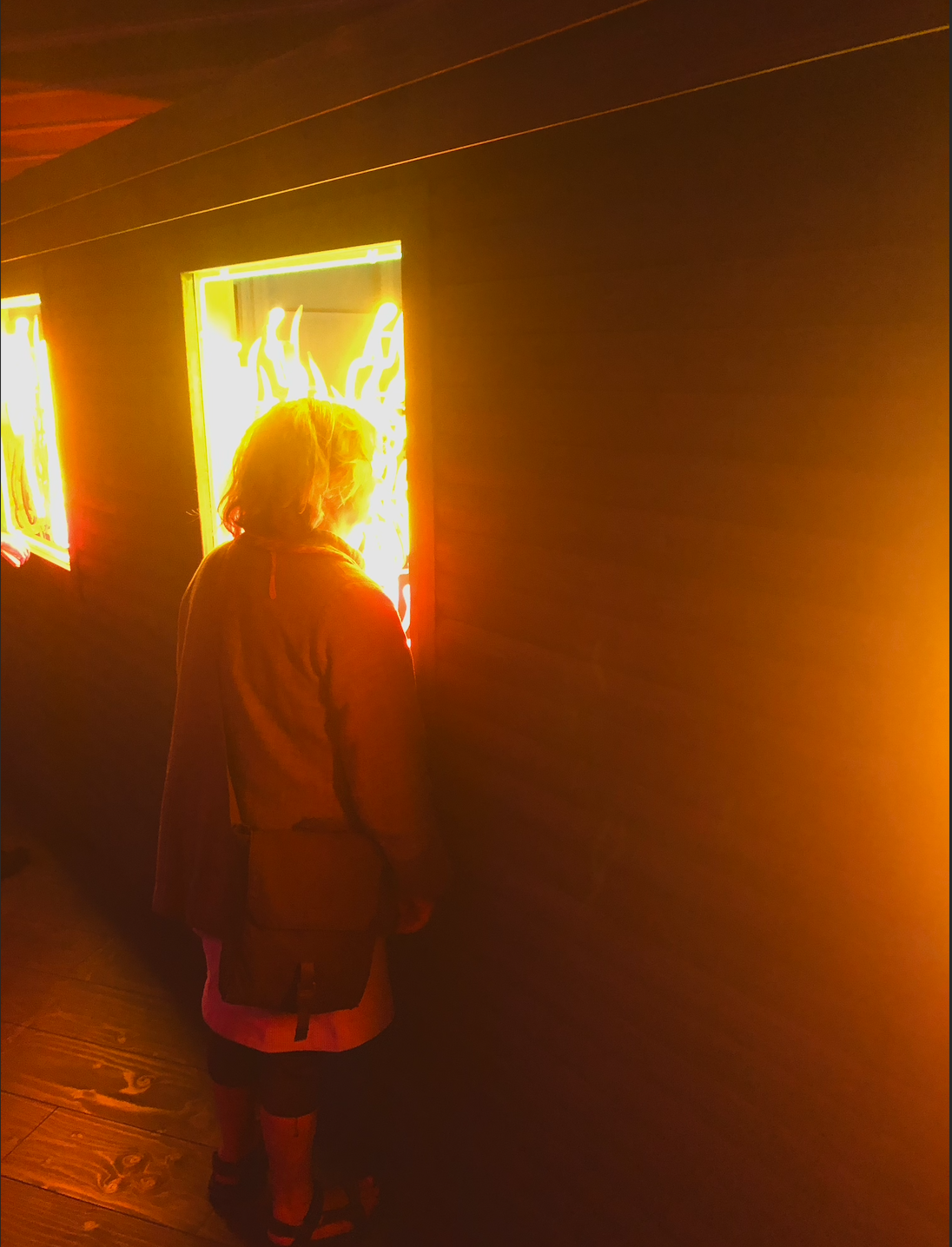

Marlene on site.

From the outside the house looked totally enflamed, but when one looked inside everything turned grippingly blue — even momentarily crippling in its insularity.

Da Corte configures his films mostly around cultural references and pop culture, and tends to disguise himself to impersonate public figures and personas. (Here, Eminem.)

Extreme kinship spotted among the spectators.

The museum is kind of marked into two sections by a beautiful cafe beside the sea. Maybe I’m romanticizing the restaurant because Malene and I had such a nice time there together, but it was special for me and I know for her as well. She bought us both coffees and these goofy strawberry cakes which are apparently very Danish, and very tasty.

Bee-guest.

We sat there talking for about an hour and a half. I could sense that there was a special two-way admiration which is only strengthened by its unexpectedness. There was also an interesting sense of attachment that I could tell we both felt toward one another, in the more practical sense that we were each other’s only reliable companions at this volunteer situation we’d both committed to. But despite likewise having rich lives in the present and past, I could sense that we were also both coming from some newfound loneliness.

Our time in the cafe had been one of those intervals of time that you know is sacred before it even ends, and as it ends you want to hold on to something more than whatever memory ends up preserving, and instead you just have to find some redemption within its fleetingness.

Another from the scattered permanent collection.

It’s cool upside down as well.

The penultimate exhibit was about Forensic Architecture, centered in the idea of The Witness. Basically, the technique uses elements of architecture, like representation of three dimensionality and analyzing physical capacities of structures, in order to investigate crime and conflict. More abstractly, it works within the notion that all matter, not only people, has “memory”, which can be recalled through spacial perception, and in turn that everything is a kind of witness.

“Reenactments:

Police reenactments are often. ritualistic events forming part of an admission or confession, denoting justice fulfilled. In the world of Forensic Architecture, reenactments are investigative processes, often made to question or prove the impossibility of official narratives. They are real-scale experiments which make memory practices more collective and participatory. They are another form of situated testimony delivered within an architectural setting as the performance of bodies in space. Architecture provides the synthesis that brings together movements and voice, trace and image: when reenactments are performed at the real site rather than a reconstruction, the space of incident turns into a model of itself.”

We ended in the incredibly extensive and rich Diane Arbus exhibit, where we stayed until we had absolutely saturated ourselves.

A couple included quotes of hers:

“I wanted to see the real differences between things… between flesh and material, the densities of different kinds of things: air and water and shiny. So I gradually had to learn different techniques to make it come clear. I began to get terribly hyped on clarity.”

“I work from awkwardness. By that I mean I don’t like to arrange things. If I stand in front of something, instead of arranging it, I arrange myself.”

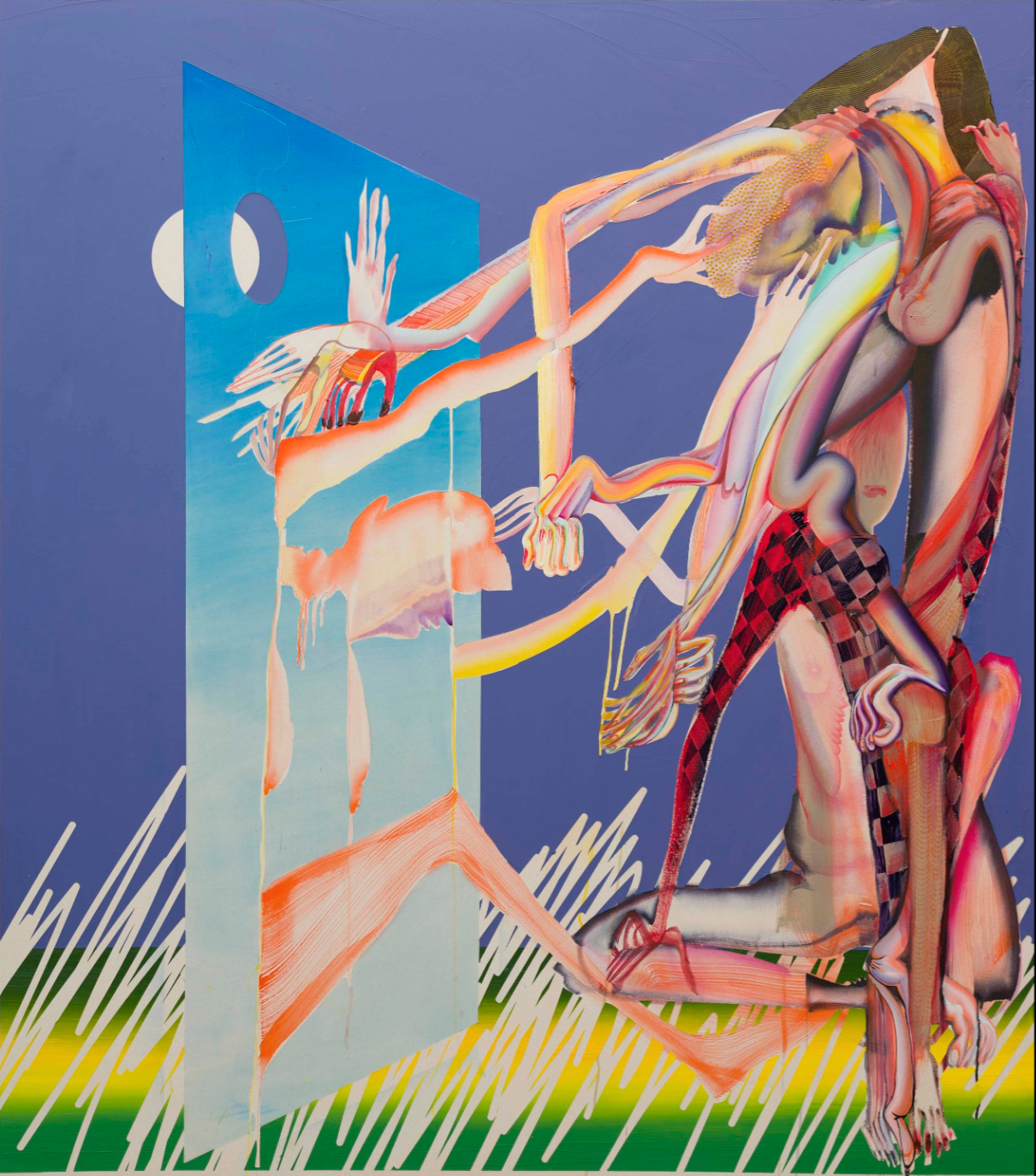

A piece by Christina Quarles that immediately intrigued me. Unfortunately she had no other works exhibited, but I will include some others taken from her website because I think they are just incredible.

Helsingør: to be continued.